ABERYSTWYTH

Click here for a copy of full the report

SUMMARY

Aberystwyth was founded in 1277. The town was laid out with a grid-pattern of streets and was provided with a stone wall for protection. A survey of 1305 records 147 burgages. This seemed to be the maximum number attained in the medieval period; in the sixteenth century there were only 60-80 inhabited houses. Other than a handful of very small investigations there has been no archaeological excavation in the town.

KEY FACTS

Status: Town charter, weekly market, two annual fairs.

Size: 147 burgages in 1307. Capacity for many more within the town walls.

Archaeology: A handful of very small investigations with poor results.

LOCATION

Aberystwyth occupies a low-lying headland on Cardigan Bay immediately to the north of the Rheidol estuary (SN 580 815), Ceredigion. The Rheidol and Ystwyth valleys provide routeways to inland Ceredigion and further east. The A487 coastal road gives access to Cardigan to the south and to north Wales to the north.

HISTORY

Aberystwyth is a planned town, created by King Edward I’s charter of 1277. Initially called Llanbadarn Gaerog (fortified Llanbadarn) after the church and monastic site of Llanbadarn Fawr located 2 km to the east, it acquired its current name in the fifteenth century.

The Anglo-Normans gained a toehold in north Ceredigion in the early twelfth century and built two castles. The site of one is well-attested, the location of the second is the subject of debate. However, Edward I considered both sites unsuitable for his new castle and town; he selected a low headland immediately to the north where the River Rheidol enters the sea. Construction of town defences was rapid. By 1278 a town ditch had been created and two years later a start was made on the town walls. By 1278 a mill had been built and in 1281 a weir on the Rheidol to provide fish for the inhabitants of the new town had been constructed. Progress was not smooth; in 1282 the Welsh destroyed the castle and town walls and five years later they burnt the town.

Settlers were encouraged into the new town, and unlike Cardigan, Carmarthen and other towns to the south where Welshmen were not welcome both English and Welsh burgesses were recorded in Aberystwyth during Edward I’s reign. The town defences provided physical protection for the townspeople and economic protection was provided by the granting of a weekly market, two annual fairs and other rights and privileges.

The town was not initially provided with its own church; worshippers had to walk or ride to Llanbadarn Fawr 2km distant. It was not until the mid-fifteenth century that St Mary’s was built close to the castle and sea. In 1762 it was reported that coastal erosion had destroyed the church many years previously.

The population of the town in the first decades following its foundation, and indeed later in the medieval and early modern period, is difficult to assess. In 1298-1300 141½ burgages are recorded but in 1300-01 only 120 of these were occupied. A few years later in 1305 there were 147 burgages; it is not recorded how many of these were occupied.

Late medieval and early modern documents paint a picture of a town that did not achieve its full potential: in the late fifteenth/early sixteenth century vacant burgages accounted for part of the £8 8s 6d rent that could not be collected; in 1539 Aberystwyth was only able to muster 68 males between the ages of 16 and 68, compared with the 372 from Carmarthen and 160 from Tenby; in the 1540s the taxable wealth of the town was only 9% that of Carmarthen; and in Elizabeth I’s time only 60-80 houses were inhabited.

Lewis Morris’s c.1740 sketch map marks the ruins of the castle and the ruins of the church, the town walls (some sections along the sea apparently destroyed) and houses within the town walls. Although just a sketch, the map does seem to show much vacant space within the walls and no houses outside them. As late as the early-nineteenth century a little undeveloped land remained in the historic core of the town, as shown on the Llanbadarn Fawr tithe map of 1845 and John Wood’s town plan of 1834.

MORPHOLOGY

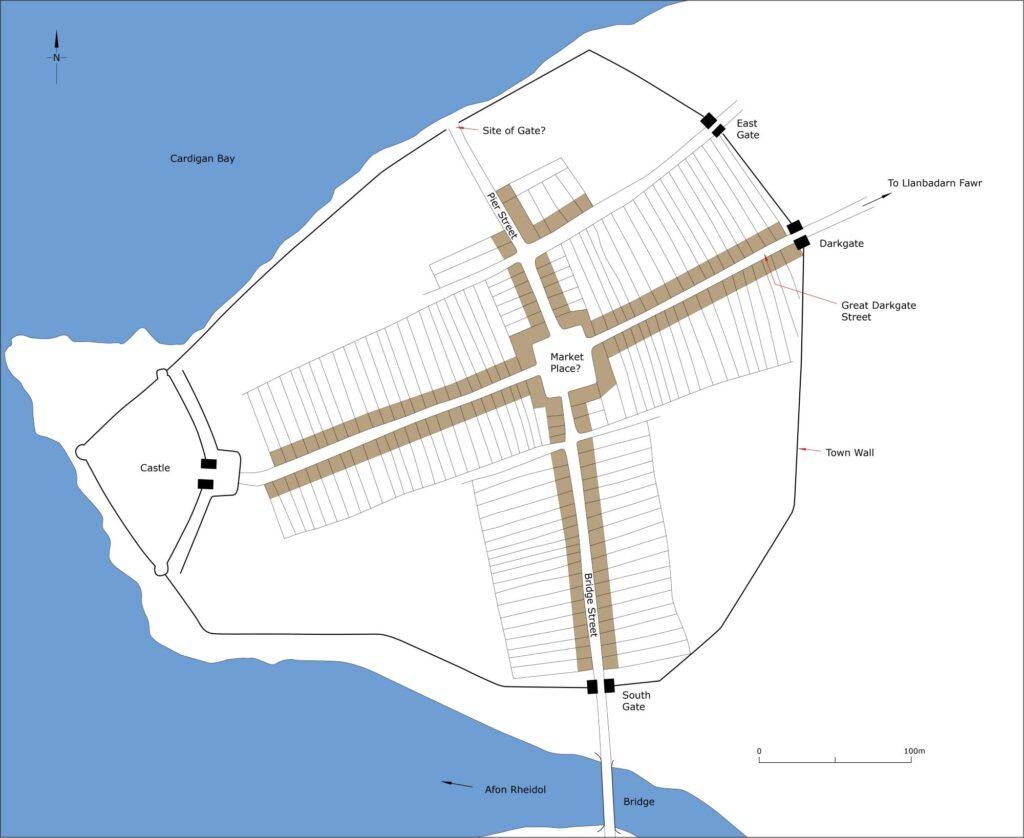

Conjectural plan of Aberystwyth in c.1320.

Although low-lying, Aberystwyth is naturally well defended. It is bounded by the sea to the north and west and by the Rheidol estuary to the south. Flat ground to the east and northeast is now built up, but until the end of the eighteenth-century parts of it would have been marsh, perhaps subject to occasional tidal inundation – Morfa Swnd lay to the north and Morfa Mawr to the east and southeast.

The town has similarities to those in North Wales founded by Edward I at the end of the thirteenth century; essentially it consisted of a grid-pattern of streets enclosed within town walls anchored by a substantial stone-built castle. Two main streets, Great Darkgate Street running roughly east/west from the castle and Bridge Street/Pier Street running roughly north/south form the main axes of the town on which the grid-pattern of streets is aligned. These two main streets were undoubtedly laid out at the town’s foundation. They meet at a slightly offset cross-roads; the reason for this offset is unclear, but this may have been the site of the medieval marketplace and was thus a small open area rather than just an intersection of streets. A town hall is recorded as having stood here in the early modern period. It is unclear whether the other streets were laid out at the town’s foundation or whether they originated in more recent times, perhaps as late as the nineteenth century. Certainly, the 147 burgages recorded in 1305 could be accommodated on Great Darkgate Street, Bridge Street and Pier Street. All writers on the history of Aberystwyth note that the course of the medieval town wall is easily traceable in the modern street pattern, though there is no extant evidence for it or the town gates. The exact line of the town wall at the junction of Sea View Place and South Road was noted during the cutting of a watermain trench in the 1950s. Elsewhere its exact line is not known. On the north side of the town foundations of a thick, mortared wall was noted in the 1970s during road works crossing Pier Street on a line roughly following the centre of King Street. Further to the west the wall may have been lost to the sea. Here (close to or under what is now called the Old College) St Mary’s Church was destroyed by the sea. It is assumed that the church was within the town walls and so it is also assumed that the walls at this location were also destroyed.

All authorities place the town gates at the east end of Great Darkgate Street, the south end of Bridge Street and the east end of Little Darkgate Street (now Eastgate). Apart from the obvious modern name it is unclear why a gate should have stood on Little Darkgate Street quite close to the one on Great Darkgate Street. A more obvious location for a third town gate would be on Pier Street close to the sea.