PEMBROKE

Click here for a copy of the full report

SUMMARY

King Henry I granted a town charter to Pembroke in 1100. The town grew rapidly, extending east from the castle along Main Street. The morphology of Pembroke indicates that the early town was provided with defences. The population continued to grow and burgages were laid out further along Main Street to the east and in the late thirteenth century walls were constructed around the whole of the town. In 1326-7 238½ burgages were recorded, giving a population of over a 1000. There have been no large-scale archaeological investigations in the town, but significant and deeply stratified medieval and later deposits were recorded during an evaluation in burgages near the castle.

KEY FACTS

Status: 1100 town charter.

Size: 1326, 238½ burgages.

Archaeology: There has been little archaeological investigation in the town, but work close to the castle has revealed deeply stratified deposits.

LOCATION

Pembroke occupies a low limestone ridge on the Pembroke River, a branch of Milford Haven Waterway in south Pembrokeshire (SM 986 014). The castle lies on the western tip of the ridge, with the town extending eastwards along the crest of the ridge. The shores of the Waterway have experienced considerable industrialisation since the early nineteenth century, but prior to that Pembroke lay within an agricultural landscape consisting of some of the richest farmland in Wales.

HISTORY

In 1093 Roger de Montgomery invaded southwest Wales and established a castle at Pembroke. There is no direct evidence for occupation at Pembroke prior to the Anglo-Norman conquest, but Roger seems to have made straight for Pembroke suggesting he was keen to acquire an important pre-existing site. Roger was succeeded by his son Arnulf. He granted the church of St Nicholas ‘within his castle at Pembroke’ to the Norman abbey of St Martin, Séez, and soon after he founded Monkton Priory to the south of the castle. However, in 1100 King Henry I stripped Arnulf of all his holdings. Henry issued a charter to Pembroke, creating a mayor, burgesses and freemen, which acted as an incentive for immigrants from the west of England and Flanders to settle in the incipient town. In 1138 Gilbert de Clare was created Earl of Pembroke, and from then until the 1536 Act of Union the fledging county palatine of Pembroke was administered from Pembroke Castle, further promoting the commercial function of the town. Pembroke was unique in never being attacked during the Welsh/English wars that characterised much of twelfth/thirteenth century southwest Wales.

The commercial importance of Pembroke is evidenced by the town charter which commands ‘all ships with merchandise which enter the port of Milford (Milford Haven) and wish to sell or buy on land shall come to the bridge at Pembroke and buy or sell there’. Clearly this document demonstrates that a bridge on the north side of the town was built soon after the town’s foundation; a bridge linking Pembroke to Monkton to the south soon followed. A tide mill is recorded on the north bridge in 1199 and one on the south bridge by the fourteenth century.

William Marshall was confirmed Earl of Pembroke in 1199 and he and his sons were responsible for building much of the masonry castle we see today, with later work, including the wall to the outer ward, completed by William de Valance who held Pembroke from 1247 to 1296. Although the history of the castle is well documented the town is not. St Mary’s Church was almost certainly founded during the early years of the town to serve the growing population. By 1291, and probably several decades earlier, a second church, St Michael’s, was founded to serve the expanding town. A new marketplace was laid out with burgages on either side. It has been argued that William de Valance began construction of the walls surrounding the whole of the town in the late thirteenth century and his son, Aymer de Valance, completed them in the early fourteenth century. In 1324 220 burgage plots were recorded, climbing to 238½ in 1326-7, giving a population well in excess of 1000.

Monkton Priory as noted above was founded in the late eleventh century. It is likely that a small settlement developed close to the Priory, separate from Pembroke but linked to the fortunes of the town and castle. Monkton had been granted two fairs by the 1480s. The Priory was dissolved in 1593.

The later medieval history of the town has not been researched, but like other towns in southwest Wales it declined due to the European-wide population crash of the mid-fourteenth century. John Speed’s map of 1611 shows extra-mural settlements, but he reported ‘more houses without inhabitants than I saw in any one city throughout my journey’ and George Owen writing a few years earlier described Pembroke as ‘very ruinous and much decayed’. With the Act of Union in 1536 Pembroke lost most of its administrative function and its maritime trade had by then suffered as Haverfordwest had become the principal port on the Milford Haven waterway; both were later eclipsed by the foundation of the towns of Milford Haven and Pembroke Dock.

It was not until the late eighteenth century and nineteenth century that Pembroke experienced an upturn in its fortunes. Modern development has been outside the historic core of the town.

MORPHOLOGY

Pembroke occupies a long, narrow limestone promontory, with the castle sitting on its western point. The town essentially consists of one long street, Main Street, running east/west along the spine of the promontory. In the medieval period tidal inlets flanked the north and south side of the promontory, providing superb natural defences for the town and castle; the inlet on the south side has been drained but the north side remains a tidal lake.

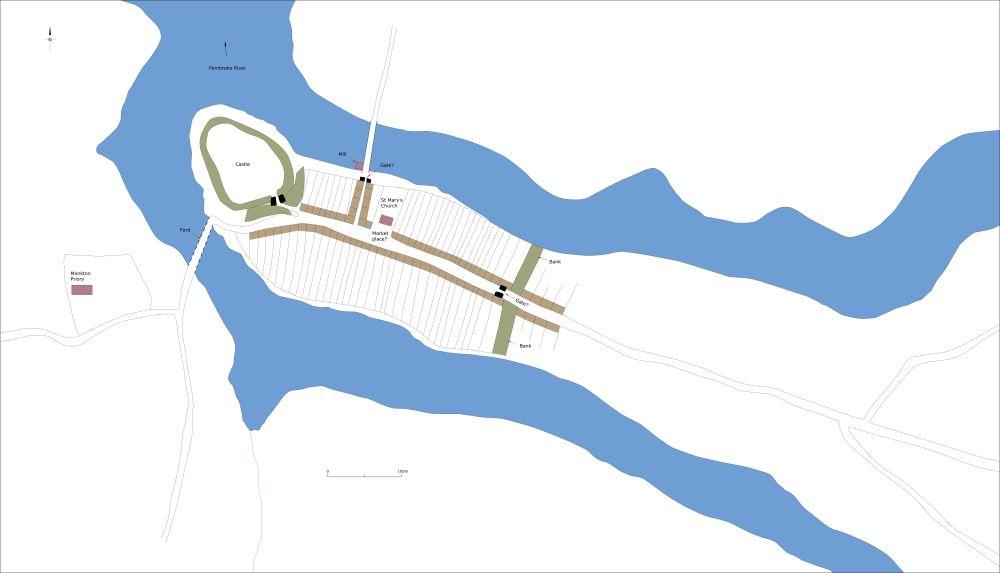

Conjectural plan of Pembroke c.1150.

The castle is one of the largest and best preserved in the region, stone-built and dating mainly to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, comprising an inner and outer ward, a massive, circular keep and a substantial south-facing gatehouse. Initially the castle would have been protected by earth and timber defences. It is likely that the first settlers could have been accommodated in the castle’s outer ward, but Henry I clearly had ambitious plans for Pembroke and it seems probable that in the first decade of the twelfth century burgages were laid out along Main Street from the castle gates. The extant coherent pattern of burgages stretching 400m from the castle gates to the east indicates that this was the first phase of the planned town. Approximately 80 burgage plots were laid out, but it is unlikely that all would have been immediately taken up by settlers; many may have lain vacant for decades. This planned town included St Mary’s Church and a bridge over the river to the north. The location of the marketplace is unclear but it may have been outside the castle gates or at the junction of Main Street/Dark Lane where Main Street widens slightly. In order to attract settlers this planned town must have been provided with defences – this would have been where the promontory is at its narrowest 400m from the castle. Certainly, it would have been a simple matter to construct a bank and ditch across the promontory at this point and rely on the steep slopes and flanking water courses to provide natural defences to the south and north. There is a slight dip in Main Street 400m from the castle which could be caused by an infilled ditch of these defences. However, it has been suggested that the Marshalls constructed a defensive bank and ditch at this location in the early thirteenth century, and that the earliest town would have been very small enclosed by a town defence lying between Dark Lane and the castle.

The town rapidly expanded. In order to accommodate the growing population new burgages were created further east along Main Street – as many as 80 new plots were laid out. This was a planned development, evidenced by the consistent size of the plots, which are slightly wider than those to the west, and by the creation of a wide, cigar-shaped marketplace on Main Street (now partially infilled by houses). The date of this new planned development is unclear, but pre-dated the foundation of St Michael’s Church, which was provided for the new townspeople, and is first recorded in 1291; map analysis shows that the churchyard was carved out of pre-existing burgage plots.

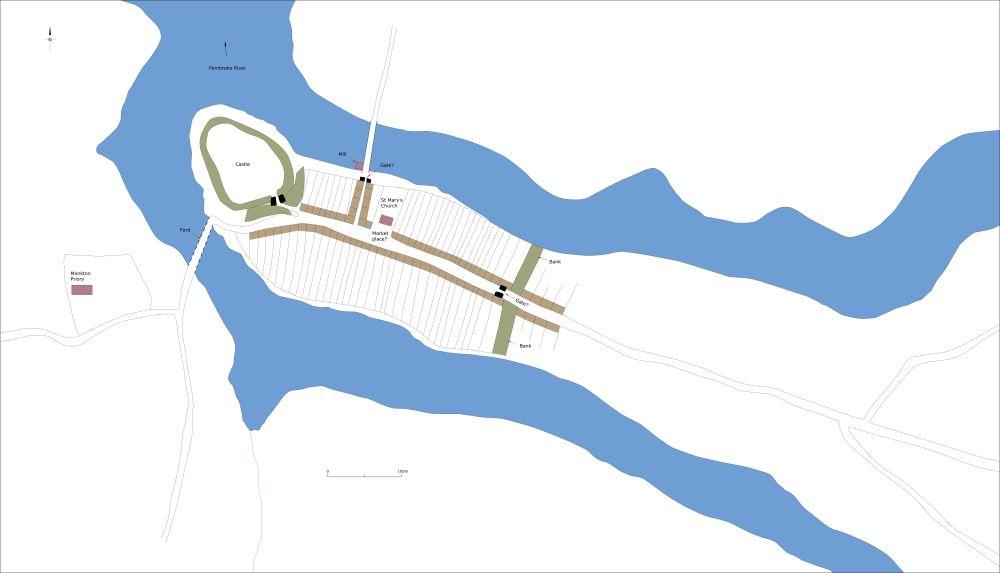

Conjectural plan of Pembroke at its maximum extent in the medieval period, c.1320.

The town was probably provided with the extant stone-built defences in the late thirteenth/early fourteenth century. There is no documentary evidence to support this, but later records refer to rebuilds and repairs to the walls. Not all the town was within the defensive circuit; in 1326-7 238½ burgages were recorded, of which approximately 160 were inside the walls. The remainder lay outside the East Gate and to the north of the north bridge. Other houses lay close to Monkton Priory to the south of the castle. 1326-7, or soon after, marks the high point of medieval Pembroke; depopulation soon occurred.

Although Pembroke was an important medieval port there is no evidence that it ever possessed a quay. Pembroke’s sheltered location and high tide range meant it was possible to load and unload ships moored on the foreshore.

The medieval town walls of Pembroke and the burgage plots, mainly defined by stone walls, are some of the best-preserved examples in Great Britain, despite some amalgamation since the nineteenth century and all effort should be made to conserve them for future generations.