TENBY

Click here for a copy of the full report

SUMMARY

A town was founded at Tenby following the Anglo-Norman conquest of southwest Wales in the late eleventh/early twelfth century. Following a period of organic growth, a grid pattern of streets was laid out enclosed by a town wall, most of which survives. In common with other towns in the region Tenby declined from the mid-fourteenth century, but nevertheless it was a wealthy settlement, evidenced by the splendid late medieval parish church. Small-scale investigations have revealed the potential for the survival of significant archaeological remains.

KEY FACTS

Status: Town charter, weekly marked and annual fair.

Size: 1320s-30s, 252 burgages and over 130 other rent payers.

Archaeology: Several small-scale evaluations, watching briefs and excavations.

LOCATION

Tenby occupies a sheltered position on the west side of Carmarthen Bay, south Pembrokeshire (SN 136 005); a north-facing shoreline provides a good natural harbour. Tenby castle lies on a rocky isthmus with the town on a slightly higher plateau immediately to the west. There are good road communications to the west and north to the medieval towns of Pembroke and Haverfordwest.

HISTORY

A tenth century poem, Etmic Dinbych, indicates the presence of a settlement at Tenby, but what form this took is unknown. The Anglo-Normans established a castle at Tenby during their conquest of southwest Wales in the late eleventh/early twelfth century, although the first reference to it is not until 1151. A settlement would have rapidly developed outside the castle and around the harbour; a port is mentioned in early twelfth century documents. St Mary’s parish church was founded in the twelfth century.

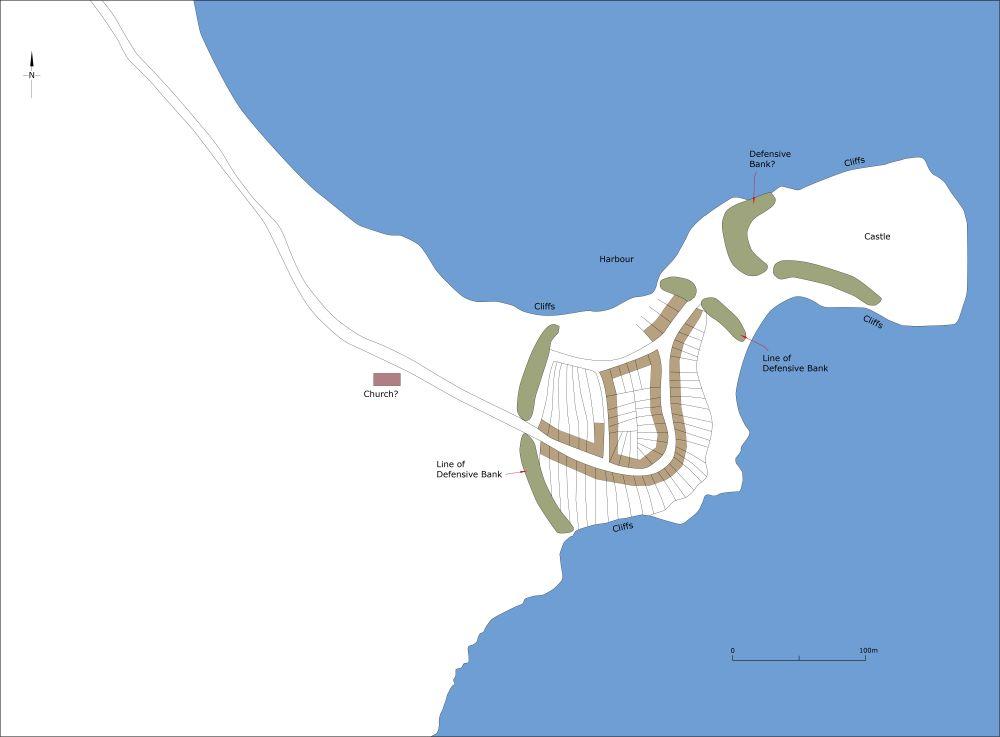

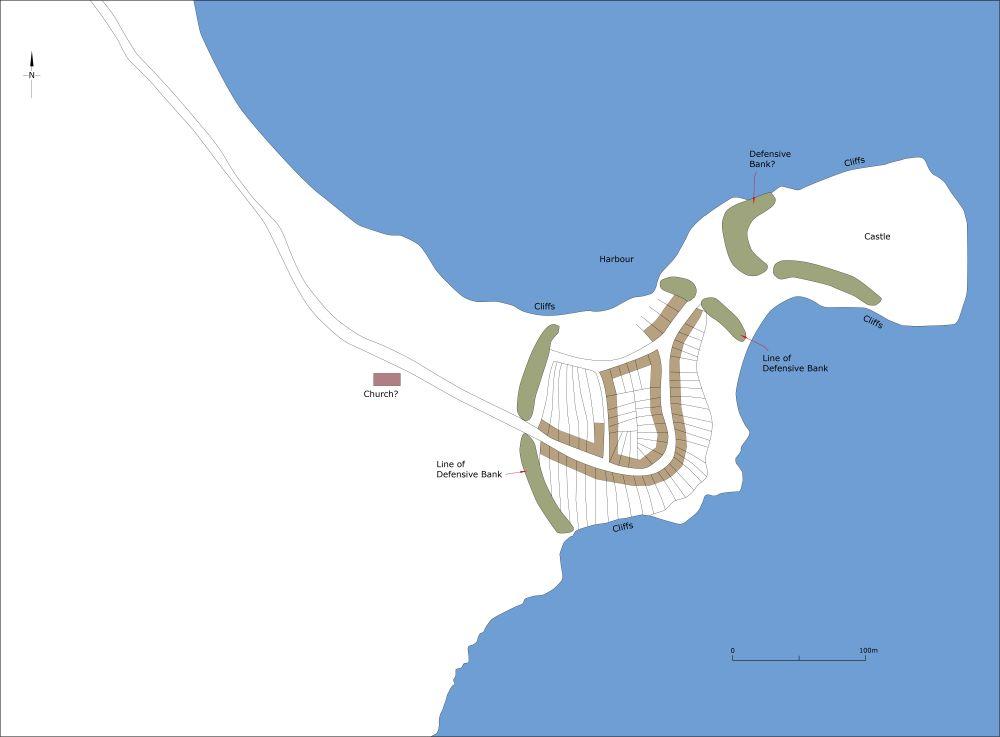

Map showing Tenby as it may have been in 1130. Note the defensive bank protecting the town is entirely conjectural, but it is inconceivable that a town as important as Tenby would not have been provided with defences.

Welsh forces led by Maelgwn ap Rhys attacked and burnt the town in 1187. It has been argued that that the townspeople erected a defensive bank topped with a timber palisade following this attack, the line of which was followed when stone-wall defences were built sometime during the thirteenth century. These were strengthened several times, most notably by Jasper Tudor in the 1450s. Two main gates were provided, the South Gate and North Gate, with a third gate, Whitesands Gate, leading to a beach by the castle and a fourth gate giving access to the harbour. The documentary evidence is a little confusing, but there seems to have been two harbour gates, an upper and a lower one, with the latter close to a substantial stone tower, called by some authorities the Harbour Tower, and which stood until the eighteenth century.

The town’s earliest known charter dates to around 1290, the rights of which were modified in later charters, including a grant to hold a weekly market and annual fair.

The size and population of Tenby in the twelfth century are not recorded. In 1245 there were 212½ burgages, in 1307 there were 241 burgages plus rents paid by six ‘burgesses of the wind’ (burgesses who did not have full rights of other burgesses) and twenty other rent payers, and by the 1320s-30s there were 252 burgages, 36 ‘burgesses of the wind and up to 100 others. Documentary sources record population decline following the Black Death in the mid-fourteenth century and by 1585 only 187 of the available 256 burgages were rented, the remainder were presumably vacant plots.

Almost all burgages lay within the town defences, but ribbon development had grown outside the North Gate at Norton, outside the South Gate and outside the Whitesand Gate (also called the Laston Gate) where, in 1434-5, six burgages were destroyed by the sea in what was known as the ‘east town’.

St Mary’s Church developed from a relatively small, thirteenth century building of nave, chancel, and south aisle to, by the end of the fifteenth century, one of the largest and most magnificent parish churches in Wales, testimony to wealth of the town in the later medieval period despite the decline in population from the mid-fourteenth century. A college founded to the west of the church in 1496 was dissolved in 1547. Two hospitals, both founded in the thirteenth century, lay some distance from the town to the north: the leper hospital of St Mary Magdalen (the ‘Maudlins’) and St John for the poor and sick. An almshouse possibly dating to the thirteenth century was said to have stood on the High Street. Two chapels lay within the town: the seamen’s chapel of St Julian which stood on the stone pier and a chapel on St Catherine’s Island.

Maritime trade was the foundation of Tenby’s wealth and thus having a safe harbour was essential. A stone pier was standing in the thirteenth century and remained, presumably much modified, until 1842 when it was incorporated into a much larger structure. St Julian’s Chapel on the pier was demolished during these nineteenth-century building works.

Tenby experienced severe decline from at least the seventeenth century. In 1676 it was reported that ‘the port and towne of Tenby is very near come to utter ruine and desolation; theire houses fallen down, the peere for preserving shipping in danger to fall into decay’. The 1810 census recorded a population of just 800. An 1809 map by Thomas Budgen shows much of Tenby within the walls occupied by houses, but most of Lower Frog Street, and parts of Upper Frog Street and St Mary’s Street were vacant. It is tempting to suggest that these areas had been abandoned since the mid-fourteenth century. Norton had developed into a long, linear suburb, but to the west of the town were fields with just a couple of houses shown on the map. However, just twenty years after the 1810 census the population was 2100 and Tenby had reinvented itself as a tourist resort

MORPHOLOGY

Tenby Castle occupies a rocky limestone isthmus with the town lying to the west. On the north side is a good natural harbour and sea cliffs provide natural protection to the north, east and south. It is assumed that the tenth century settlement recorded in the Etmic Dinbych occupied the rocky isthmus later used for the castle, but this is not certain.

The curving St Julian’s Street, Bridge Street and several narrow irregular lanes and passageways on gently sloping ground immediately to the west of the castle and south of the harbour form the earliest part of Tenby town. This was an unplanned settlement that grew organically. Some writers considers that this is a pre-Anglo-Norman settlement, which if correct would be unique in southwest Wales, although it is perhaps more likely to have developed following the Anglo-Norman conquest in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries. There is no documentary, archaeological or topographic evidence indicating that this early settlement was ever defended, but it is inconceivable that it was not, and it would have been a simple matter to provide it with an earthwork bank and ditch running north/south from cliff to cliff.

The creation of a marketplace (Tudor Square), the establishing of St Mary’s Church and laying out of burgages either side of the marketplace and High Street was a second, planned, phase of development, during the twelfth century.

A third and much more clearly planned phase was the creation of a grid pattern of streets flanked by burgages – St Mary’s Street and Upper and Lower Frog Street. At the same time a new defensive circuit was constructed, the course of which is followed by the extant medieval town walls. It has been suggested that originally this defensive circuit consisted of an earth bank topped with a timber palisade, which was laid out soon after the burning of the town in 1187. These defences would have protected a town of about 250 burgages, a sizable town for late twelfth-century west Wales, and while it is not impossible that the townspeople had ambitions for the growth of Tenby at this date, the resources to do so may have been beyond them, and thus it is more likely that the planning of the grid pattern of streets and creation of defences belongs to the thirteenth century.

In the medieval period the town was confined within the town walls. The only exceptions were burgages outside the North Gate at Norton and the ‘east town’ which lay outside the Whitesand Gate, and where six burgages were destroyed by the sea in 1434-5. The exact location of ‘east town’ is unclear, but presumably the burgages were close to the seashore south of the castle. Indeed, the exact locations of the Whitesand Gate, the ‘Harbour Tower’ and the Lower Harbour Gate, all of which must have clustered above the harbour close the castle are unclear as nothing now survives of them.

Most domestic buildings in the town date to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The exceptions are the National Trust owned ‘Tudor Merchant’s House’ and neighbouring buildings to the north of Tudor Square which contain late medieval and early modern elements.

In the early modern period houses were built either side of the road leading out from the North Gate at Norton, but it was not until the nineteenth century that extensive development took place outside the town walls.